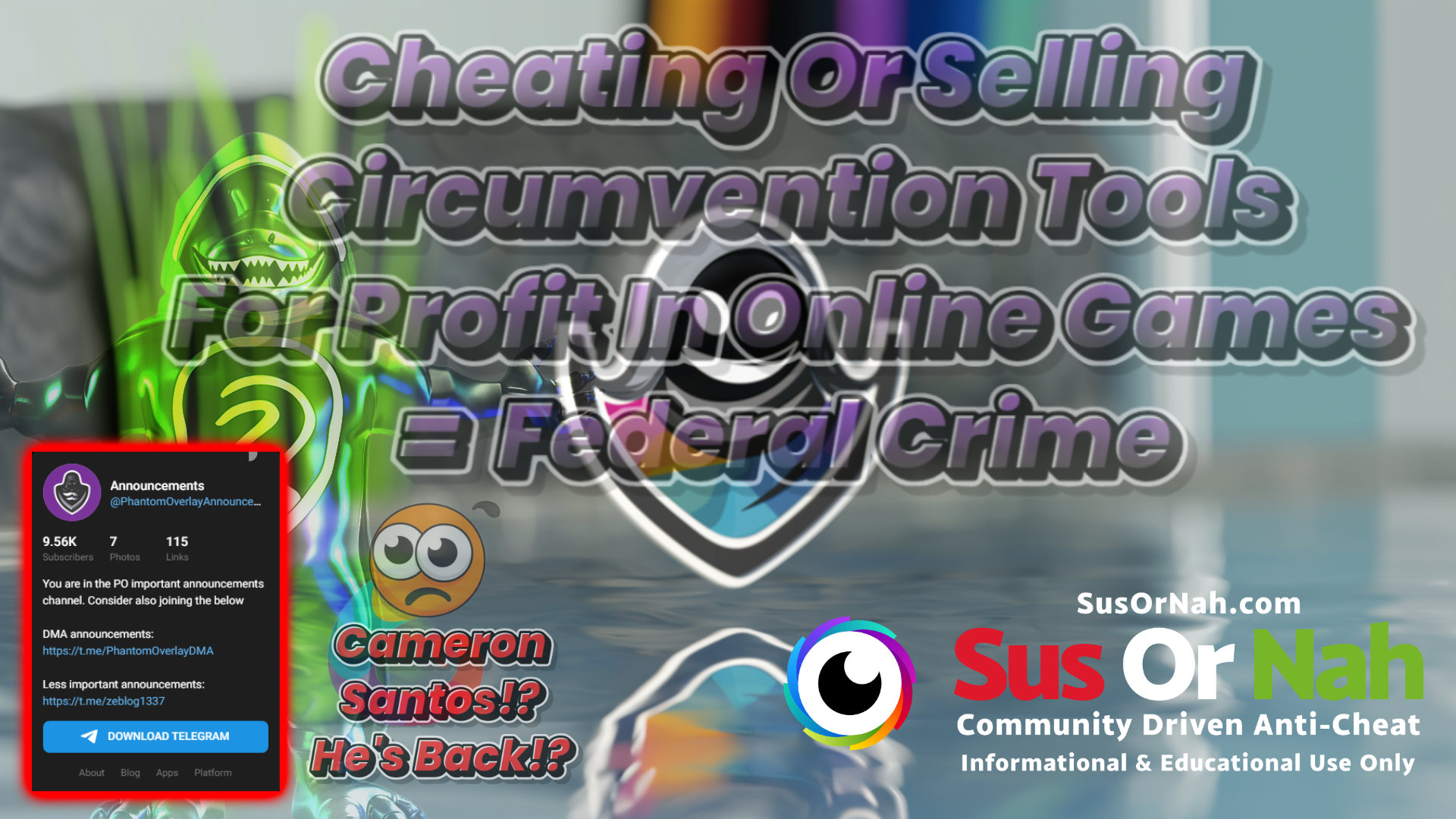

Recent community reported information indicates that Cameron Santos a New Mexico Resident has restarted operations at PhantomOverlay.io, a business he launched soon after encountering legal difficulties. Formerly a cheat developer for GatorCheats who faced legal action, Santos is reportedly circumventing detection by Activision by using anonymous domain registration to conceal his activities. In recent years, the video game industry has experienced an increase in cheating practices, with some individuals not only participating in unfair gameplay but also profiting from creating and selling cheat software. There's a prevalent but mistaken belief among these individuals that their activities are safeguarded by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This article intends to clarify this misconception and explain why such activities actually amount to wire fraud, a serious federal crime with significant legal repercussions.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” While this amendment provides broad protections for various forms of expression, it is not an absolute shield against all forms of speech or conduct.

Courts have consistently recognized limitations on First Amendment protections, particularly when the speech or conduct in question is integral to criminal activity. In United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285 (2008), the Supreme Court held that offers to engage in illegal transactions are categorically excluded from First Amendment protection. This principle is directly applicable to the creation and distribution of cheating software for video games, especially when done for profit.

To understand why cheating in video games and profiting from such activities constitutes wire fraud, it is essential to examine the legal definition and elements of this offense. Wire fraud is codified in 18 U.S.C. § 1343, which states:

“Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, transmits or causes to be transmitted by means of wire, radio, or television communication in interstate or foreign commerce, any writings, signs, signals, pictures, or sounds for the purpose of executing such scheme or artifice, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.”

The key elements of wire fraud are:

When individuals create, distribute, or use cheating software in video games for financial gain, their actions align closely with the elements of wire fraud:

a) Game developers and publishers: By circumventing the game’s intended mechanics and security measures, cheaters undermine the integrity of the product, potentially causing financial harm through decreased player engagement and retention.

b) Other players: Honest players are defrauded of a fair gaming experience, which they have paid for and reasonably expect.

c) Digital marketplaces: Platforms that host these games may suffer reputational damage and financial losses due to the proliferation of cheating.

a) Distribution of cheating software through online platforms

b) Online payment processing for the sale of cheats

c) The actual use of cheats in online multiplayer games

Several legal cases have established precedents that support the classification of video game cheating for profit as wire fraud:

Proponents of cheating software often attempt to invoke First Amendment protections, arguing that the creation and distribution of such software constitute protected speech. However, this argument fails on several grounds:

1. The Commercial Speech Doctrine and the Central Hudson Test:

The sale of cheating software, being primarily an economic activity intended to generate profit, falls under the purview of commercial speech. While the First Amendment protects commercial speech, this protection is not absolute and is subject to greater restrictions compared to political or artistic expression. The seminal case of Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, 447 U.S. 557 (1980), established a four-part test to determine the constitutionality of restrictions on commercial speech.

The Central Hudson test requires that: (1) the speech in question must concern lawful activity and not be misleading; (2) the asserted governmental interest in regulating the speech must be substantial; (3) the regulation must directly advance the governmental interest asserted; and (4) the regulation must not be more extensive than is necessary to serve that interest.

Applying this test to the sale of cheating software reveals several points of contention. Firstly, the inherent nature of cheating software raises concerns regarding its legality and potential for misleading consumers. By design, it circumvents the intended rules and mechanisms of online games, often violating terms of service agreements and potentially constituting fraud, especially in games involving monetary wagers. Secondly, governments have a substantial interest in protecting the integrity of online marketplaces, including the gaming industry, from fraudulent activities and unfair competition that undermine consumer confidence and disrupt fair play.

Therefore, regulations aimed at curbing the sale of cheating software, by demonstrating a clear connection between the software and unlawful activities like fraud and demonstrating that such regulations are narrowly tailored to address the specific harm, would likely pass the Central Hudson test and withstand First Amendment scrutiny.

2. Speech Integral to Criminal Conduct: The Giboney Precedent:

The Supreme Court, in Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 U.S. 490 (1949), established the principle that speech integral to criminal conduct is not afforded First Amendment protection. This exception applies when the very act of communication is inextricably intertwined with illegal activity, rendering it unprotected.

Applying this principle to cheating software requires a nuanced analysis. If the software is specifically designed, marketed, and utilized to facilitate criminal activities, such as online gambling fraud or the unauthorized access and manipulation of game servers, then its creation and distribution could be deemed integral to criminal conduct and fall outside the scope of First Amendment protection. However, if the software possesses legitimate, non-fraudulent applications, such as game modifications for personal use or development purposes, then the argument for applying the Giboney precedent weakens considerably.

3. Expressive Content versus Functional Software: The Brown Distinction:

The Supreme Court, in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, 564 U.S. 786 (2011), recognized video games as a form of expressive content protected by the First Amendment, citing their capacity to communicate ideas and convey messages through interactive storytelling and artistic elements. However, this recognition does not necessarily extend to cheating software.

Unlike video games, the primary function of cheating software is not to convey a message or express an idea. Rather, its purpose is purely functional: to alter the operational mechanics of a game to provide an unfair advantage to the user. While some might argue that the design and implementation of such software could involve elements of creativity and expression, these aspects are ancillary to its primary, functional purpose. Therefore, it is unlikely that cheating software would be afforded the same level of First Amendment protection as video games, as its primary function is not expressive in nature.

4. Terms of Service Agreements and Contractual Waiver:

Most online games operate under detailed terms of service agreements (TOS) that users must accept before accessing the game. These agreements typically contain clauses explicitly prohibiting cheating, the use of unauthorized third-party software, and other activities that undermine fair play and the integrity of the game environment. By agreeing to these terms, users enter into a binding contract with the game provider, consenting to abide by the stipulated rules and limitations.

Courts have consistently upheld the enforceability of TOS agreements, including clauses prohibiting cheating. These rulings establish that users, by agreeing to the TOS, effectively waive certain rights, including any purported right to cheat or utilize unauthorized software. Consequently, even if cheating software itself were to enjoy some degree of First Amendment protection, users could still be held liable for violating the contractual obligations they agreed to in the TOS.

The impact of cheating in video games extends beyond legal considerations, affecting various stakeholders in the gaming ecosystem:

The cumulative economic impact of cheating in video games is substantial. A report by Irdeto, a digital platform security company, estimated that the video game industry loses up to $29 billion annually due to cheating and piracy.

While the legal framework for prosecuting video game cheating as wire fraud exists, enforcement presents several challenges:

To address these challenges, a multi-faceted approach is necessary:

The notion that the First Amendment provides a defense for cheating in video games and profiting from such activities is fundamentally flawed. These actions clearly constitute wire fraud, a serious federal offense. The development, distribution, and use of cheating software in video games for financial gain meet all the elements of wire fraud: a scheme to defraud, intent to defraud, and the use of interstate wire communications to further the scheme.

Legal precedents and established limitations on First Amendment protections further support this conclusion. The commercial nature of cheat distribution, its integral role in criminal conduct, and its primarily functional rather than expressive purpose all preclude First Amendment protection.

The widespread economic and social impacts of cheating in video games underscore the importance of addressing this issue through legal means. While enforcement challenges exist, a coordinated approach involving international cooperation, public-private partnerships, legislative updates, and community education can effectively combat this form of cybercrime.

As the video game industry continues to grow and evolve, it is crucial that legal frameworks adapt to protect the integrity of games, the rights of developers and publishers, and the experience of legitimate players. Recognizing video game cheating for profit as wire fraud is an important step in this direction, providing a clear legal basis for prosecution and deterrence.